Dispatch from a Revolution of Sugar and Blood

The predatory vengeance of Jean-Jacques Dessalines: Installment 1

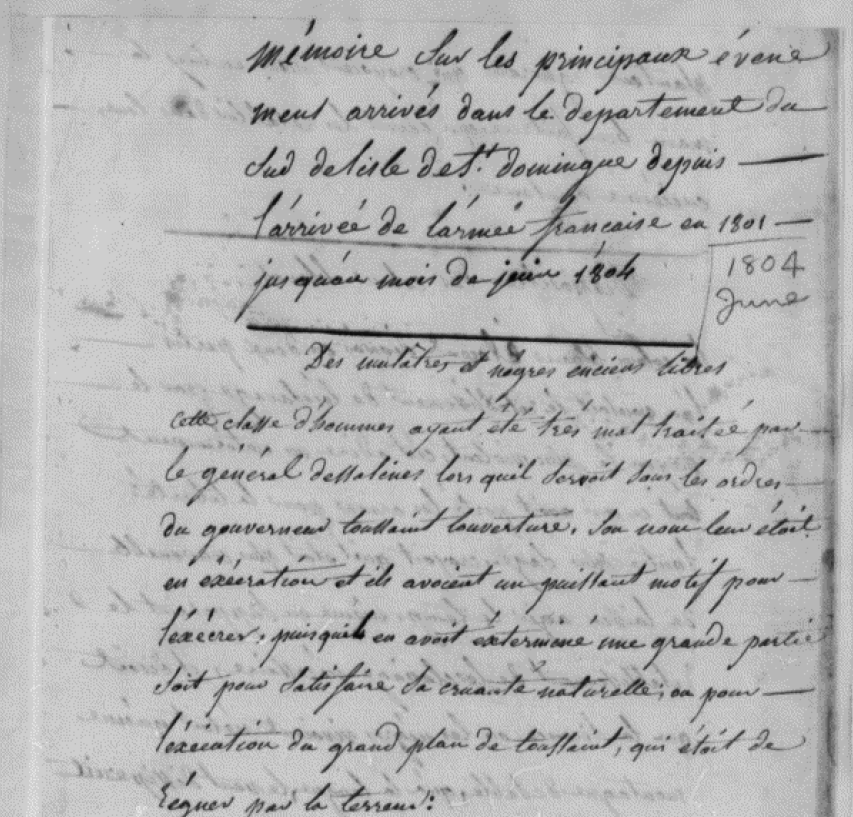

In the papers of Thomas Jefferson, housed in the Library of Congress, a mysterious diplomatic dispatch has lived for over 200 years. The hand that penned “Decout” in June of 1804 never signed its name, and the eyes to whom the dispatch was addressed are not identified. (It is possible that “Decout” referred to Jefferson’s acquaintance Jean Decout, but the name appears nowhere on the 12-page document). In chapter 4 of The Devil Lives in Haiti I rely on an isolated piece of its diplomatic intelligence to establish the living hostility between agents of the French and those of the British in 1801-1804, a hostility which destroys the absurd narrative of a political world united in cheerful alliance against the “unwelcome guest” of independent Haiti. In this page I plan to do justice to the document’s full importance, as a witness to the later years of the Haitian Revolution when the flag of Jean-Jacques Dessalines flew in brutal leadership over the lost promise of Toussaint Louverture. My translations may be the very first

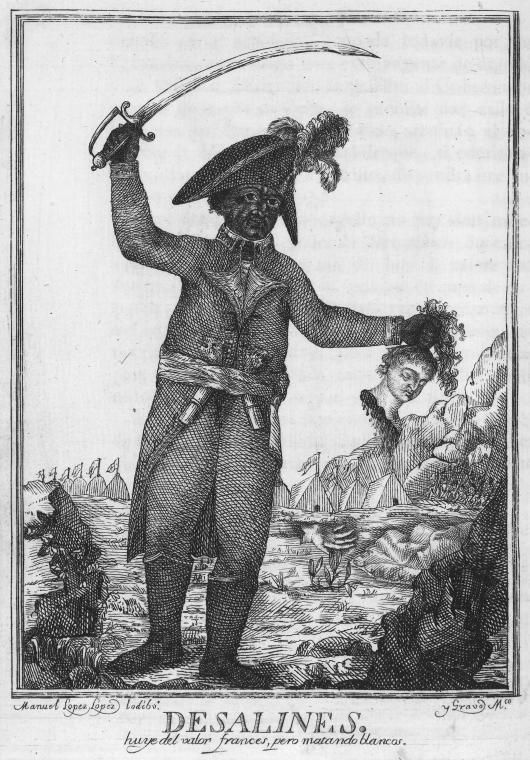

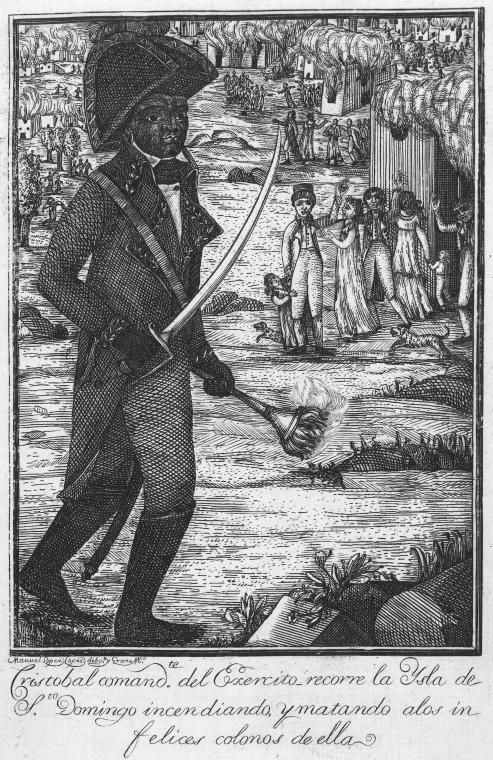

The incursions of Haitian revolutionary leadership in the 1790s and early 1800s into Spanish Santo Domingo are widely reported, including in Toussaint Louverture’s Memoire (1802-1803). It was contact with General Dessalines that inspired a Spanish witness, likely a Dominican, to immortalize the vengeance of the General in this artwork, which is housed in the digital collections of the NYPL. “matando blancos” = killing whites.

For the full original text, visit the digital collection of the Library of Congress. This document is also referenced in The Devil Lives in Haiti , and cited in Chapter 4, “An Unwelcome Guest?”

The following two paragraphs are translations of the original document, but the second paragraph translates a paragraph that does not display on page 1 of the French original. When French vocabulary cannot be deciphered beyond a guess, it is noted as “illegible.”

How does a narrative of convenience neutralize inconvenient facts?

How does a narrative of convenience neutralize inconvenient facts?

Method 1: Omission

The skeptical historian does not need to cast a stone very far before striking a bearer of mythology in Haitian studies. My stone was cast only a short distance into the pond of the internet before it struck, with predictable success, All The Devils Are Here (2020). A double standard in the representation and historical reporting of Haitian Revolution-era casualties is the theme of Marlene Daut’s online article. Comparative violence and comparative losses are weighed, and it is the thesis of Daut that the atrocities against blacks in the revolution were underappreciated by white audiences. The same atrocities against whites, it is argued, fulfilled a self-serving interpretation of inherent black monstrosity. If atrocities are the theme of this article, those of Jean-Jacques Dessalines are buried in silence.

The narrative of convenience reproduced by Daut assumes a theater of violence between noble black resistance fighters and white reactionaries, whose fortune alternates between dominance and defeat between 1791 and 1804. Nowhere in this narrative are the documented brutalities of Dessalines against non-whites, as evidenced in “Decout” above, nor are there the white-on-white atrocities between the forces of reaction and revolution. The assassination of Ferrand de Baudieres in 1789, and other white officials who shared his modest defiance of the colonial caste system, are far beyond the scope of memory in All the Devils Are Here. The field is only large enough to accommodate one Devil, and I abhor competition.

For those readers who believe the first page of “Decout” weakly suggests that Dessalines was not purely a soldier for revolutionary justice, but could have been tainted by excesses in pursuit of virtue, return for the next installment. The General’s white victims will receive the delayed justice of recognition

The Misunderstood Monster

Installment Two of The Predatory Vengeance of Jean Jacques Dessalines

The Unforgiving Dominicans

Spanish caption at right in translation: “The Army of Commandante Cristobal travels across the island of Santo Domingo, burning and killing its unfortunate settlers.”

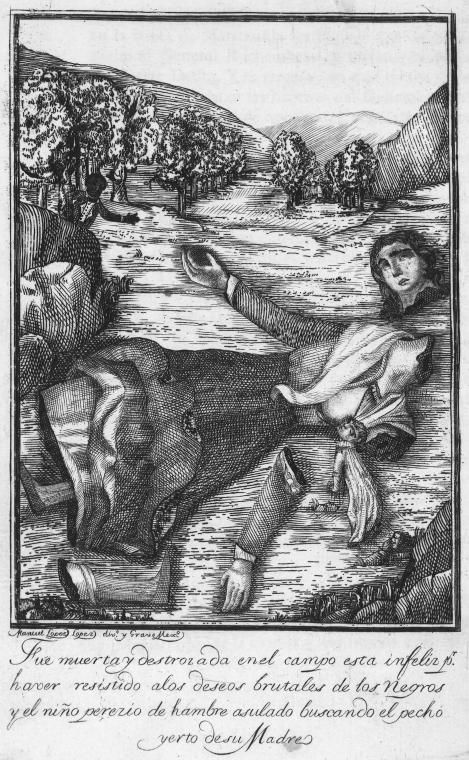

Spanish caption at left in translation: “This unfortunate lady was killed and torn to pieces in the field. She resisted the brutal desires of the Blacks, and the child died of hunger, isolated, searching for his mother’s cold breast.”

These Spanish engravings, housed in Vida de J. J. Dessalines, gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo – NYPL Digital Collections, are dated to 1806 and represent brutalities that are consistent with contemporary reports of the Haitian leadership under Dessalines, including the letter of “Decout” below. The reliability of these engravings is sound given the ample corroboration of other historical witnesses. A healthy skepticism, however, opens the question as to whether these engravings are propaganda against the occupying Haitians, a propaganda that sought to invent or exaggerate brutalities. To satisfy this doubt, however, requires internal inconsistencies as well as weak corroboration. Both of these conditions are missing, pointing to a powerful testimony of either lived experience or witnessed events.

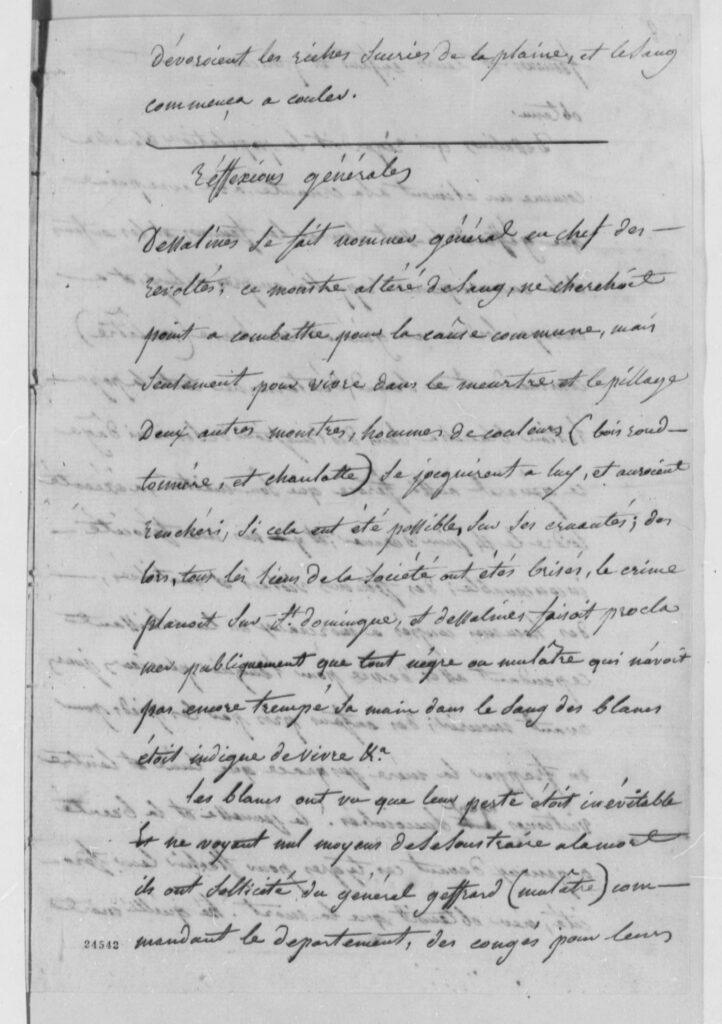

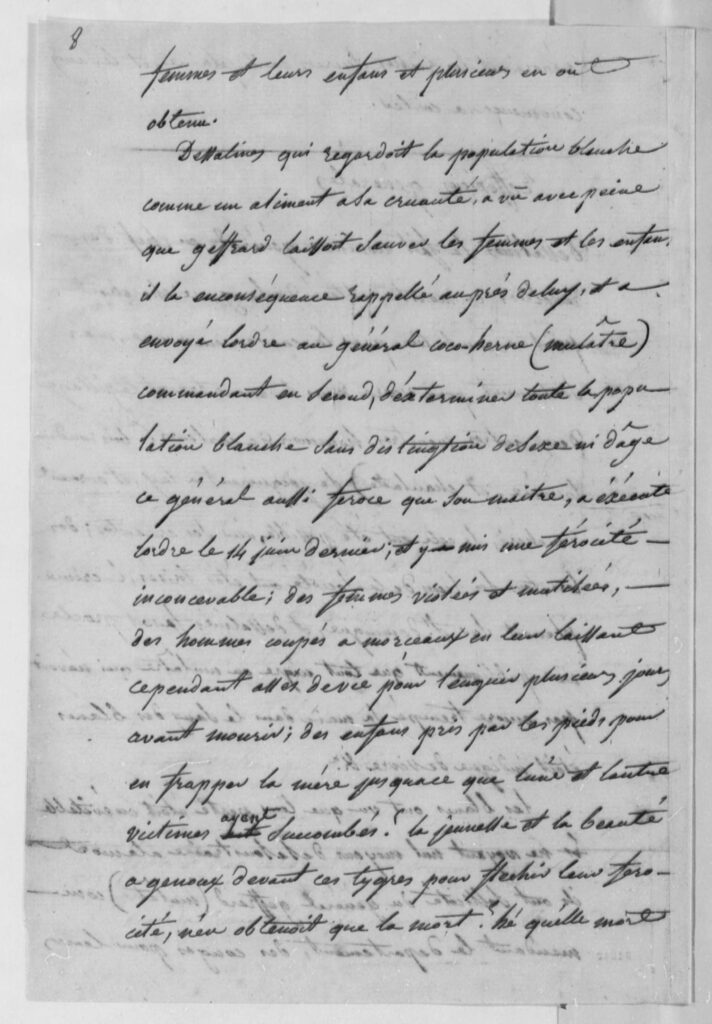

Pages 7 and 8, "Decout," June, 1804, French Original

For the full original text, visit the digital collection of the Library of Congress. This document is also referenced in The Devil Lives in Haiti , and cited in Chapter 4, “An Unwelcome Guest?”

My English Translation

The General referred to as “Deluy” is a probable translation of the original, but this item does not have as high a degree of certainty as the rest.

General [Affaires]

Dessalines had himself named chief general of the insurrectionists; this man, a monster of altered blood, was not seeking at all to make common cause but only to live in murder and pillage; Two other monsters, men of color, ([illegible] and chaulotte) would join him, and would have exceeded him if that had been possible, in his cruelties. By far all of the bonds of society were shattered. Crime was soaring over Saint Domingue, and Dessalines was proclaiming that all blacks or mulattoes who had not yet wet their hands in the blood of whites were not worthy of living.

The whites saw that their loss was inevitable, and seeing no means to escape death, they solicited General Geffrard (a mulatto), commander of the department, to save their women and children, and several of them obtained their safety.

Dessalines, who saw the white population as nourishment for cruelty, viewed with pain that Geffrard had allowed the women and children to be saved. In consequence, Dessalines called after Deluy and gave the order to Coco-Berne (mulatto), second-in-command, to exterminate the white population without distinction of either sex or age. This general, who was just as ferocious as his master, executed the order on June 14 of last year. There, he put to work an inconceivable ferocity. Women were raped and mutilated and men cut to pieces, but leaving them to live several days before dying. Children were taken by their feet to be used as striking objects against their mothers until they both succumbed. Both youth and beauty, to satisfy the ferocity of these tigers, were set to their knees, and nothing was obtained but death. [What] death, good Lord, is that which barbarism has invented most cruelly. Bosoms are sliced, eyes are torn out, and veins torn open. What tongue is so unrestrained as to express these crimes? My tears, which are still flowing, prevent me from saying a word more.

Analysis

How does a narrative of convenience neutralize inconvenient facts?

How does a narrative of convenience neutralize inconvenient facts?

Method 2: Selective Privilege

The massacres of Dessalines, amply documented by “Decout” above, are simply misunderstood. This is the thesis of Laurent Dubois, whose Haiti: The Aftershocks of History (2012) leads the academic agenda of rescuing and rehabilitating Jean Jacques Dessalines from the blood of infamy in which his sword of leadership is forever stained. How do the pages of an historian succeed in sanitizing a legacy whose atrocities of violence would be beyond reputational repair for any other chief of war either living or dead? The answer lies in the privileging of favored voices.

In the pages of The Aftershocks (42-43), the voice of Dessalines is superior to examination, corroboration, or doubt. In this privilege the myth of Dessalines as a noble, eye-for-an-eye avenger is accorded full credibility, as the historian views Dessalines through the same mirror of myth through which Dessalines viewed himself. In this glorified mirror no murder, massacre, mutilation, or torture is unjustified. The same privilege is not accorded to any other historical voices, such as the disfavored United States Naval Admiral William Caperton (243), who is subject to doubt, investigation, and the demands of corroboration.

I am not alone in recognizing and retching from the attempts at rehabilitating Dessalines. Author Guzi He, writing in 2024, Making a Hero Out of a Mass Murderer deplores the 2018 consecration of a New York City avenue to the memory of the Haitian war criminal. Guzi He tactfully addresses the myth of Dessalines and attacks the evasions of academic historians, who dance around the question of documented atrocity as they point to mitigating diversions. “Why wasn’t there blood on the leaves?” asks the academic rescuer of Jean-Jacques Dessalines. My reply is simple: there was blood everywhere else.