The Haitian Revolution Timeline at Brown University

From the citadel of academic prestige, installed on the east side of Providence, Rhode Island, the Africana Studies Department of Brown University has reproduced the narrative of convenience prevailing among historians of Haiti. The narrative enshrined in the online timeline is the citadel of an academic orthodoxy whose shake-up is long overdue. This post will illuminate the one-sided moral outrage of historians of revolutionary Haiti, the omission of historical witnesses whose reports challenge the myth of Haitian noble revenge, and the suppression of the full picture of non-white colonial slaveholding prior to 1791.

From the citadel of academic prestige, installed on the east side of Providence, Rhode Island, the Africana Studies Department of Brown University has reproduced the narrative of convenience prevailing among historians of Haiti. The narrative enshrined in the online timeline is the citadel of an academic orthodoxy whose shake-up is long overdue. This post will illuminate the one-sided moral outrage of historians of revolutionary Haiti, the omission of historical witnesses whose reports challenge the myth of Haitian noble revenge, and the suppression of the full picture of non-white colonial slaveholding prior to 1791.

The sweep of colonial and revolutionary Haitian history is the subject of Kona Shen’s online timeline, which relies at times on primary documents (See 1750s) and heavily on secondary narratives such as those of Carolyn Fick (see September, 1791). Though the ostensible purpose of the project is the reconstruction of events and movements leading to Haitian independence in 1805, the true agenda is revealed in the selectivity of sources and the privileging of black martyrdom to the suppression of black opportunity and complicity in the colonial order. The narrative of convenience, attacked by myself in The Devil Lives in Haiti, enjoys perfect dignity in the citadel of academic myth.

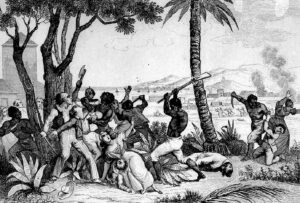

The blood of massacre appears faded and obscure when viewed from a safe distance. The aversion of academic historians to the documentary witnesses of the 1790s sustains the distance that keeps the narrative of convenience alive. Absent from Shen’s timeline are the first-person accounts of Michel-Etienne Descourtilz (1795) and Bryan Edwards (1802), both of whom speak with the volume they deserve in Chapter 3 of The Devil Lives in Haiti. The massacre of children and the weaponization of rape and mutilation, documented abundantly in the 1790s, defeat the myth of noble revenge to which Shen and her academic supporters are still attached.

Non-white slaveholding in colonial Haiti is recognized by Shen in a brief introduction to “French Rule and Tensions in the Colony: 1750-1784.” This inconvenient subject is soon buried in a selective narrative of the French colonial order. The truth of non-white slaveholding in fact deserves volumes instead of passing recognition. Absent from the timeline are the names of Julien Raymond, Jean-Baptiste Mongol, Marthe Guillaume, and Depas-Medina. These are among thousands of colonial, free people of color, featured at length in Chapter 2 of my work, whose slaveholdings rivalled the most prosperous whites, and whose wealth humiliated the petty ambitions of landless colonial whites.

The standard of moral outrage in Kona Shen’s timeline of history is simple to decipher: atrocities against those of color are deplorable. The same atrocities against whites are the necessary costs of a revolution in pursuit of noble revenge. The martyrdom of Ferrand de Baudière, a white judge who paid with his life for the advancement of racial equality, receives anonymous, fleeting, pathetic recognition in the opening segment of the timeline (1750-1789). The massacre of ex-slave “noncombatants” in January of 1792, however, is reported in gruesome detail. The “ruthless violence” of Rochambeau, in November of 1802, again merits an expansive condemnation, relying on the secondary narrative of Carolyn Fick. The only martyrs honored by Shen, whose agenda enjoys the implicit support of Brown University, are those martyrs whose blood feeds the narrative of convenience.

If a double standard prevails in academic interpretations of the Haitian Revolution, no leader enjoys the benefits of this standard more than Jean-Jacques Dessalines. When the documented violence of this successor to Toussaint Louverture, a successor whose atrocity is too baldly documented for even the most ardent apologist to ignore, it is bathed in a mitigation and exoneration which Dessalines is uniquely privileged to enjoy. Dessalines’ massacre of dissident revolutionary leaders in January of 1803 is acknowledged, to the frustration of Shen’s pursuit of the narrative of convenience. Dessalines’ extraordinary privilege in the eyes of academic historians is revealed in the justification that follows the description: those dissidents, in the secondary interpretation of Carolyn Fick, were enemies of liberty. No attempt is made to investigate the truth of this claim, either by competing descriptions of the massacre or by competing historical accounts (however rare they may be). If Dessalines did it, then he must have had a good reason.

For those still attached to the image of Jean-Jacques Dessalines as a noble avenger, I encourage all readers to view “The Vault” page of this website. I will be discussing a fascinating diplomatic dispatch, whose English translation is long overdue, which puts the myth of noble revenge into the same inglorious resting place reserved for the victims of Dessalines’ persecutions.